- Home

- Knowledge Insights

- Expanding Green Finance in Sri Lanka’s Financial Services Sector

Developing countries currently account for just 1.6 billion US dollars of the estimated 33 billion US dollars in outstanding green loans, even as many of these countries are some of the most vulnerable to climate change but also have the biggest investment needs in drive nature-positive economic growth[i]. In Sri Lanka, there is now a growing interest in the concepts and prospects for green finance among Sri Lankan policymakers, regulators, and financial intermediaries, and some initial steps have been made to orient towards green lending. Yet, how far has actual implementation come and what are the prospects for the near-term? What are some of the critical issues that the financial sector must contend with, as it aims to support investments in a climate-resilient and nature-positive economic recovery? We explore some of these themes in this article, and provide ideas for action.

Understanding green finance

In traditional banking, when a bank makes a loan it considers certain factors about the client to determine the loan’s financial impact to its bottom line – what the funds are for, the repayment capacity, the borrower’s financial standing, tenor, pricing and overall risk are considerations a bank would make. Environmental considerations would not be a factor that is considered, except if environmental clearances are needed by the borrower’s project. Under green financing, however, it goes much beyond.

Green finance involves collecting funds for addressing climate and environmental issues (green financing), on the one hand, and improving the management of financial risks related to climate and the environment (greening finance), on the other[ii]. Green finance is simply a financial structure, such as a loan, designed to achieve environmental outcomes[iii]. A green loan, as further defined by the IFC (2023), ‘…is a form of financing that enables borrowers to use the proceeds to exclusively fund projects that make a substantial contribution to an environmental objective’. Such loans are strictly tagged with use-of-proceeds clauses, governed by the Green Loan Principles and the Green Bond Principles (GBP) of the International Capital Market Association (ICMA). These specify that 100% of the proceeds should be used only for green eligible activities. Other global standards, frameworks or best practices have been published by the Sustainable Banking and Finance Network (SBFN)[iv] and the Equator Principles Financial Institutions (EPFI)[v], which are membership-based and aim to improve standardization, adoption and technical capacity among industry players.

Even as there is difficulty for green projects to get the financing they need, evidence from the region suggests that the capital does exist. The Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2023[vi]observed that there is sufficient global capital and liquidity to close the global investment gap. However, lenders have been slow to orient themselves to the needs of the market. This is a finding emerging from ongoing assessments being done by CSF for the Sri Lankan market, but we are not the only country facing this challenge. As a UNESCAP (2023)[vii]report noted, “The slowness of banks in Asia and the Pacific to commit to net zero and transition their lending and investing portfolios with interim 2030 science-based targets is a serious brake on driving finance towards climate action in the region”(p.6).

Multilateral banks and development partners need to work closely with the banking sector to leverage more private capital and de-risk projects. As observed in UNESCAP (2023), “A 1:5 ratio, like ADB’s goal, can be one benchmark to ensure that concessional funds truly leverage private finance and go towards well-structured projects. This will also guarantee well-designed projects in which concessional finance truly catalyzes and mobilizes greater private finance”(p.7). In Sri Lanka, much of these partnerships up to now have largely focussed on SME concessional lending (refinanced schemes, at lower interest) or at most, renewable energy credit lines. In fact, an online review of products on offer show that most of the ‘green loans’ by Sri Lankan banks tend to be for purchasing energy-efficient equipment (solar power systems, EVs, biogas units, etc.), rooftop solar deployment (with relatively small ticket-sizes) and medium-scale non-conventional renewable energy generation (i.e., wind or solar farms). These now must expand to the full gamut of not only mitigation projects, but also adaptation activities where private sector investment has potential.

The role of private capital in financing adaptation cannot be forgotten. As is clear from recent data, public financial flows simply are not able to meet the large and growing needs. A UNEP (2023) report released ahead of the recent COP28 summit revealed that, ‘Adaptation finance needs of developing countries are 10-18 times as big as international public finance flows – over 50 per cent higher than the previous range estimate’[viii] – The current adaptation finance gap is now estimated to be between 194 – 366 billion US dollars per year, while developing countries experienced a 15% decline in public multilateral and bilateral finance flows for adaptation in 2021. The Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) has reiterated that, in light of ongoing fiscal tightening by the government, “…fiscal support on incentivising the financial sector for adopting sustainable financing initiatives is rather limited…”, and that, “…it is expected that the private sector will take the initiative to explore […] climate financing options”(p.52)[ix].

For a highly climate vulnerable country like Sri Lanka, the banking sector cannot only focus on mitigation finance (for instance, supporting an energy transition by lending to renewable energy projects), it must necessarily also finance adaptation. This would range from lending for regenerative agriculture, nature-positive tourism projects, reef-positive fisheries enterprises, and manufacturing that adopts circular business models. The financial services industry needs to recognize the risks posed by climate change, and that the risks permeate to the financial sector. According to the World Bank, climate change will approximately cost Sri Lanka an annual GDP loss of 1.2% by 2050[x].

In fact, in its latest Financial Stability Review 2023[xi], the CBSL had an explicit section on ‘Mitigating the Impact of Climate Risk on Financial System Stability’, demonstrating that the highest regulatory authorities are increasingly concerned about this. It noted that, ‘Both physical and transition risks of climate change are linked to price stability and financial system stability of an economy where the physical damages will result in low production leading to increase in price levels while financial institutions will be exposed to increasing non-performing assets due to unsustainable business activities being financed’(p.52).

Policy and regulatory progress

Some early steps have been made that lay a foundation for further action in Sri Lanka. In 2015, the Sri Lanka Sustainable Banking Initiative (SL-SBI) was launched by the Sri Lanka Banks Association in[xii]. More recently, the regulator has also taken initiatives to help catalyze action. In 2019, the Central Bank of Sri Lanka (CBSL) launched its ‘Roadmap for Sustainable Finance’ that broadly proposes an action plan for regulators and financial intermediaries to follow. This was complemented with the ‘Sri Lanka Green Finance Taxonomy’ released in 2022, which is a classification system to define and categorize economic activities that are environmentally sustainable. While these are essential steps to finance climate change action, such policies are not currently mandatory, and so adoption of these policies by financial intermediaries vary widely.

The regulator has also issued directions and guidelines to FIs regarding sustainable financing and banks have begun reporting sector-wise sustainable lending. Accordingly, it is estimated to be just 1% of the total lending portfolios of banks by mid-2023. This reporting is expected to get more robust with the release of the green finance taxonomy, and the adaptation of International Financial Reporting Standards (IFRS) S1 and S2 on sustainability-related financial information and climate related risks. In an encouraging message that the financial services industry should wholeheartedly welcome, the CBSL has noted that it “…may consider granting regulatory forbearances/ incentives for the financial institutions who are committed to greening their portfolios and support the transitioning of the country into a green economy”[xiii].

Connecting intent with action

Globally there is to be a growing disconnect between what banks say and what banks do. In an incisive 2023 report on ‘Green lending: do banks walk the talk?’[xiv], staff at the European Central Bank observed that among 100+ institutions they studied in the Eurozone, banks which portray themselves as more environmentally-conscious lend more than others to ‘brown industries’, and that there is sharp disconnect between the extent of ‘green disclosures’ by the banks and their actual lending to green projects.

Sri Lankan regulators and industry players should take notice, because the disconnect appears in Sri Lanka too – albeit not studied as empirically as in the Eurozone. Simply adding the colour green to the institution’s logo, or the mention of environmental principles in an Annual Report message by the Chairman or CEO, does not demonstrate advanced adoption of green lending and environmental integration in practice. Some early research on some of these aspects for Sri Lankan financial institutions (FIs) are emerging.

Evidence from Sri Lanka

A recent CSF assessment of environmental integration[xv] in Sri Lanka’s financial services industry showed that (of the 56 FIs that were assessed[xvi]) while 22 firms’ demonstrated environmental integration intent[xvii], only 12 of them refer to adherence to national policy frameworks and guidelines[xviii], and of them only 7 refer to international guidelines[xix]. Moreover, only 4 FIs mention any environmental targets in alignment with a strategy or regulatory guidance. The research also found that just 8 FIs had adopted an internal policy or strategy focused on the environment, while 12 reported having dedicated internal resources (for instance, a “climate task force”, “ESG team” with emphasis on the environment, a “sustainability officer”, or other environmental related committee, sub-committee, or management team). Encouragingly, 12 FIs reported taking steps to build staff capacity building on environmental integration. It was revealing that not a single FI mentioned having an external inquiry/complaint/ grievance mechanism related to its ‘ESG’ or ‘environmental practices’, which is a vital component in building credibility in, and stakeholder engagement in making improvements to, its activities. Basic environmental impact reporting seems to be more widespread, though, with 27 of 56 FIs explicitly reporting one or more of the following: electricity consumption, water consumption, paper consumption, GHG emissions, carbon footprint, renewable energy produced, etc. But moving beyond this basic tenet, the research found little evidence that Sri Lankan lenders systematically assess environmental impacts and risks in granting loans (5 of 47 lending institutions). The research also explored whether FIs indicate that they quantify/measure environmental and/or climate risks in their portfolio. Just 2 FIs indicate they categorize sectors most vulnerable to climate risk, and 2 indicate they review environmental risks such as ‘Transition risk’ and ‘Physical risk’ in their portfolio.

Tapping into global and domestic funding sources

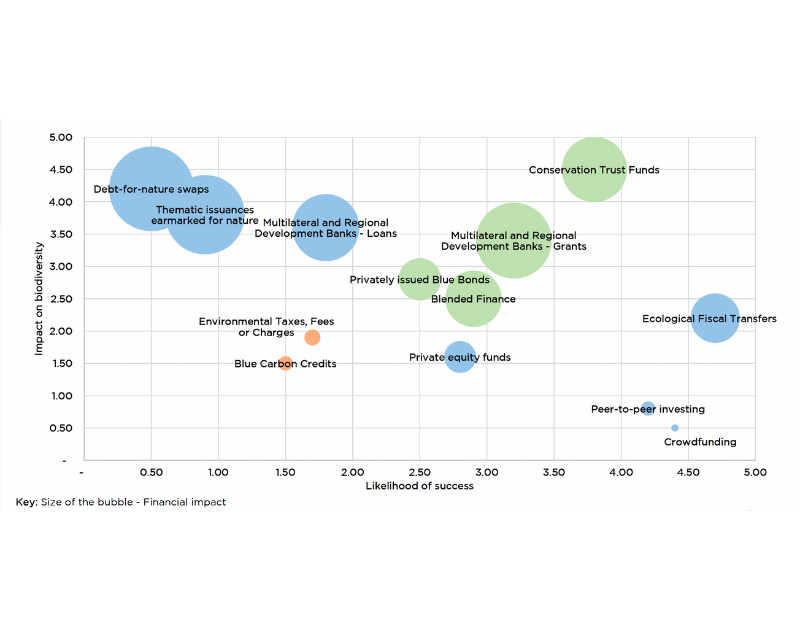

The good news for Sri Lanka’s banking sector is that the money is available – Sri Lanka just needs to know where to look and how to access it cleverly. Sustainability and green financing accounted for one-third of all money in assets under management (AUM) in 2020, according to Bloomberg[xx], and this number is only expected to have grown to date. Following the conclusion of debt restructuring and a subsequent country sovereign re-rating, funding sources are likely to steadily open up.

Already some banks have set up the foundations for accessing new sources of green finance. In July 2023, DFCC broke new ground by being the first private sector bank in the country to obtain Green Climate Fund (GCF) accreditation[xxi], with access to possible project financing between 50 to 250 million US dollars (‘Medium size’). In fact, the bank became the first so-called ‘Direct Access Entity’ in Sri Lanka[xxii], as prior to this, only the government and multilateral institutions were able to apply for, and channel money into, Sri Lankan projects from the GCF.

Some FIs have also begun introducing green deposits[xxiii], where individuals or corporates can save with the bank where their funds will specifically be allocated to the bank’s green lending portfolio (aligned to the CBSL Green Taxonomy). However, evidence of uptake and information on what specific environmental projects the proceeds will be used for are often lacking. In principle these type of products can tap into domestic sources of ‘conscious capital’ – especially high networth investors. Innovation among Sri Lankan financial institutions is urgently needed. As they develop credible and meaningful green finance products, they can access international pots of funds that are tied to sustainability and green financing AUM, and utilize these domestically for green projects. Sri Lankan banks do not need to ‘reinvent the wheel’ – they can use the typical products it has like loans or leases, but where innovation is required is to explicitly link these products to climate-positive activities and outcomes. Alongside this, the demand-side needs to be strengthened. Particularly SMEs, continue to struggle. Our demand-side assessments have shown that SMEs often lack investor readiness for green finance opportunities and may not be able to meet the reporting requirements that financial institutions require for green financing. They are also less able to face long and uncertain payback periods from green investments, along with difficulties in ensuring user demand for green products and services they provide. So, firm-level upgrading is needed to grow the demand-side.

Looking ahead

Overall, credibility will be key, as concerns of ‘green-washing’ have increased and skepticism around so-called ‘ESG practices’ have heightened. So, the credibility of the projects that funds are lent to need to be ensured, and for this FIs should look to forge partnerships with groups that can help strengthen this – for instance, organizations like Environmental Foundation, Blue Resources Trust, and Biodiversity Sri Lanka that have the technical know-how to advice on environmental integration as well as collaborate on monitoring effectiveness and impact.

Moving towards the future, there is an agenda for action for all stakeholders. For the industry, FIs need to look inwards at their internal lending capabilities and green product structuring and offerings, while continually looking at whether they are making true commitments to climate-resilience and a nature-positive economic recovery. For policymakers and regulators, a key question in the near-term would be what further regulatory and policy action would be required to accelerate authentic and innovative green finance among Sri Lankan banks and non-bank financial institutions.

Anushka Wijesinha is Co-founder/Director of CSF and Heshal Peiris is Project Associate (Conservation Finance) of CSF. Errol Abeyratne is Green Finance Specialist with Biodiversity Sri Lanka, working concurrently with CSF. The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of organisations outside of CSF that the authors may be associated with.

—

References:

[i] https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2021/10/04/what-you-need-to-know-about-green-loans

[ii]https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2021/679081/EPRS_BRI(2021)679081_EN.pdf

[iii]https://rare.org/green-finance/?gad_source=1&gclid=CjwKCAiA44OtBhAOEiwAj4gpOXuoY9KNwao9ZESpuOnh0cs8IZfcfGo2sw6EA8FVdahfzUmco2C0KhoCv44QAvD_BwE

[iv] https://www.sbfnetwork.org/

[v] https://equator-principles.com/about-the-equator-principles/

[vi] https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-cycle/

[vii]https://www.unescap.org/kp/2023/sustainable-finance-bridging-gap-asia-and-pacific

[viii]https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/press-release/climate-impacts-accelerate-finance-gap-adaptation-efforts-least-50

[ix] https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/sites/default/files/cbslweb_images/publications/fssr/fssr_2023e.pdf

[x]https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/sri-lanka-needs-100-billion-become-net-zero-emitter-by-2040-president-says-2023-11-28/#:~:text=The%20island%20also%20faces%20the,according%20to%20the%20World%20Bank.

[xi] https://www.cbsl.gov.lk/en/publications/economic-and-financial-reports/financial-system-stability-review

[xii]SL-SBI has launched a set of 11 Sustainable Banking Principles, developed by a committee of participating banks, and have since been adopted by 18 signatory banks. (Source: https://sustainablebanking.lk/)

[xiii] ibid.

[xiv] https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/blog/date/2023/html/ecb.blog231206~fecd1d1634.en.html

[xv] We defined ‘Environmental integration’ as the extent to which firms regard the environment in their financial and non-financial business decisions, and utilized a bespoke assessment tool with criteria informed by global and local frameworks and knowledge (Sustainable Banking and Finance Network ‘ESG Integration’ pillar; Road Map for Sustainable Finance in 2019; and SBFN Sri Lanka Financial Sector Country Progress Report 2022.

[xvi] For selection of FIs for the review, we used the Global Industry Classification Standard (GICS) among CSE-listed firms, and the data sources were the Annual Reports of these firms, followed by some In-depth Interviews with industry leaders to validate selected aspects of the findings.

[xvii] Assessed by the Chairmans’ or CEOs’ Annual Report messages mentioning aspects like “ESG” (with a specific reference to environmental issues), “environmental consideration(s)”, and “ESMS (Environmental Services Management System)”.

[xviii] Mentions either the CBSL Sustainable Finance Roadmap or the Green Taxonomy

[xix] Mentions one or more of the following: Task Force on Climate-related Financial Disclosures (TCFD) recommendations; Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) Sustainability standards; GRI standards from (Global Sustainability Standards Board); Sustainability Accounting Standards Board (SASB).

[xx]https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2019-green-finance/?leadSource=uverify%20wall

[xxi]https://www.greenclimate.fund/ae/dfccbank

[xxii]https://www.dfcc.lk/media/dfcc-bank-becomes-first-sri-lankan-entity-accredited-by-the-green-climate-fund-gcf-unlocking-climate-finance-opportunities/

[xxiii]https://www.dfcc.lk/products/dfcc-green-deposit/#:~:text=adverse%20climate%20changes.-,The%20funds%20raised%20via%20the%20DFCC%20Green%20Deposit%20are%20allocated,few%20examples%20of%20sustainability%20loans

image (c) Centre for a Smart Future (Anushka Wijesinha and Ruwani Rajapakse)